For this very reason, even someone well-situated to discuss North American Indian inculturation along the St. Lawrence ought to keep a respectful distance when the Indians in question live along the Amazon. However we can nonetheless stress an important universal that has been sadly absent from much of the discussion over the last 50 years. Inculturation, we are told, must respect local tradition. And that is true. But too often, only pagan or secular tradition is meant, and that is where the fatal error creeps in. What inculturation actually must respect most of all, is a culture's own Catholic tradition.

We need to go back in history, as far back as we can, to the first meeting between the faith and the culture. And then we trace how both faith and culture entwined through the centuries, creating a local Church that was the natural fusion of that process. And this applies as equally to Europeans and European-Americans as it does to American Indians or Congolese.

It is a titanic error of judgment to assume that no cultural fusion worth mentioning happened before Vatican II. And that is manifestly the case in the region served by the Zairean Use.

|

| Alvaro VI of Kongo (1581-1641) |

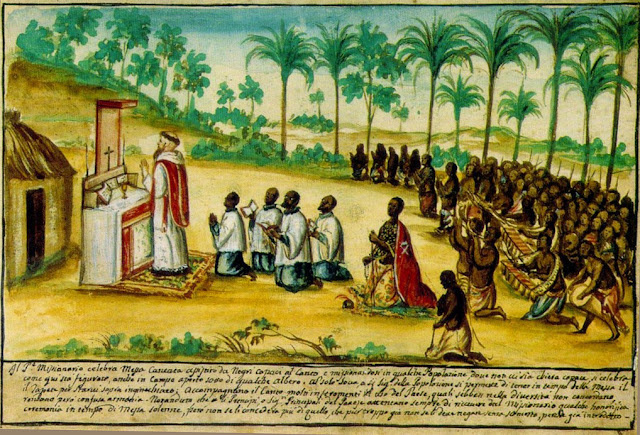

Anyone who uncritically transplants jaded European modernism into the minds of the indigenous Congolese might be surprised by that last fact. But historical accounts indicate that subsaharan Africans did not scorn the pomp and ceremony of the Baroque European liturgy—to the contrary, they seemed to have been quite eager participants in it.

The Italian chronicler Filippo Pigafetta noted in 1591 that the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in M'Banza Kongo had attached to it: “about twenty-eight canons, various chaplains, a chapel master, and choristers, besides being provided with an organ, bells, and everything else necessary for Divine service.”

|

| Ruins of the Cathedral in M'Banza Kongo. By Madjey Fernandes - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30108996 |

Missionary Girolamo Merolla (1650-1697) informs us that there were 18 churches in the dominions of the Count of Sogno. On the feast of St. James, every governor of a city was obliged on pain of deposition and a fine to either attend or send a representative to the Banza of Sogno to assist at the first Mass. A throne was set up for the Count in the marketplace. Dressed majestically in an embroidered scarlet cloak, a coral rope, a crown of feathers, and a cross of gold around his neck, the Count received a benediction from the missionaries and then demonstrated his skill with a bow and arrow as well as a musket. Military exercises then took place under his watch, and symbolic tributes were brought forth from the various areas of his dominion. “This Ceremony is begun on St. James’s day, by reason that Apostle is look’d upon as the Patron and Protector of all these Parts, and that for having given a famous Victory to the King of Congo against the idolaters on his day.” Great crowds from the surrounding areas came to partake of the festivities.

Some fascinating details are also given about the Count of Sogno’s liturgical roles during the various parts of the Mass:

“While Mass is saying, at the reading of the Gospel he has a lighted Torch presented to him, which having religiously receiv’d, he gives to one of his Pages to hold till the Consummation be over, and when the Gospel is done he has the Mass-Book given him to kiss. On festival Days he is twice incens’d with the Censor, and at the end of Mass he is to go to the Altar to receive Benediction from the Priest, who laying his Hands upon his Head while he is kneeling, pronounces some pious and devout Ejaculations.”

.png) |

| Pedro V, King of Kongo. Reigned 1859-1891. |

These fascinating tidbits of information give a tantalizing glimpse into how the medieval Roman liturgy was embraced by the Congolese court and its subjects.

They also raise an important and perhaps uncomfortable question.

How much of what passes for authentic Congolese inculturation nowadays is actually just a modern primitivist's stereotype of what Congolese liturgy ought to look like, rather than reflecting how the historical Congolese liturgy actually did look like for all its long history?

We don’t, unfortunately, have a completely clear picture of the ancient Congolese liturgy—perhaps if any of those old Portuguese Missals are still around, they might shed light upon the question.

We know that the Congolese church was suffragan to the See of Lisbon. But Lisbon’s liturgy is not even certain for this time period. Once the city was recaptured from the Moors in 1147, the Sarum Rite was established there by its first bishop: the English monk Gilbert of Hastings. Through the centuries, the Sarum Rite seems to have gradually declined until 1536 when Lisbon officially switched to the Roman Rite. But it's unclear how that switch happened, and where the last holdouts were.

|

| A History of the Church in Portugal (1759); listing the Congo/Angola (Congensis seu Angolensis) suffragan to Lisbon (Olysiponensis). |

So in the 1490s and soon afterward--well before the Council of Trent and at the tail end of the medieval era--could the first missionaries from Lisbon and their successors have been celebrating the Sarum Rite, or perhaps a Sarum-influenced Roman Rite? Could Afonso's son Henrique Kinu a Mvemba, who became a priest and then was consecrated a bishop by Leo X in 1518, have learned the liturgy?

Again, we don’t know, but these are historical possibilities. And by entertaining these possibilities, we are persuaded to abandon any facile stereotype of African primitivism, and wonder whether the court of Kongo might well have used a ritually complex medieval Ceremonial that made even today's Latin Mass parishes look very bare and austere by comparison.

Does a Congolese liturgy really have to mean the modern Zairean Use? Or can it also mean the medieval Sarum Use as well? Perhaps all our focus on developing a new liturgy has distracted our attention from something far older and roots that run much deeper: a priceless liturgical heirloom still waiting to be discovered in a Congolese archive.