In my online 'travels' I frequently come across new projects, sanctuary arrangements, renovations and restorations. Having long been an advocate of ad orientem, the ciborium magnum (and other forms of canopying the altar, not to mention the reredos), I am often on the lookout for how these are being implemented as much as I am whether they are being implemented.

Sanctuary design is not for the faint of heart in this politicized, post-conciliar liturgical environment where every design choice seems micro-analyzed, subject to debate and to the decisions of a diocesan bureaucracy. Debates rage about ad orientem and versus populum, central tabernacles (or not), altar rails, the placement of the sedilia, etc. On it goes. Though the environment is certainly less hostile now than it was twenty years ago for those who seek to restore a classical arrangement, it is not yet tranquil by any means. I have little doubt that this climate will fade and mostly disappear within the next 20-40 years, but until that happens these are things that the faithful, parish priests and liturgical artists simply have to work with as best they can. That said, a politicized climate is not the only challenge that can present itself in this regard.

Another issue that can arise is the matter of Eucharistic reductionism. Put at its simplest, this is the very pious sense that everything revolves around the tabernacle (i.e. the Blessed Sacrament). At face value this seems to make sense: the Blessed Sacrament is the Real Presence of Jesus Christ, so why wouldn't that be hierarchically topmost after all? But the reality is that it is not "tabernacle and sacrament" that have the central-most place in Catholic liturgical thought and architecture, it is rather "altar and sacrifice" -- and why is obvious once explained: the Mass is the sacrifice of the Cross, re-presented and perpetuated, truly and really; it is the salvific act and what is most primary and it is upon the altar that this is accomplished. It is upon that altar that the sacrifice of Christ is renewed (and, what's more, it is from there to in which we are brought the sacrament of the Eucharist). All flows from this. All flows from the Mass which is the source and summit.

One of the laudable goals of the Liturgical Movement was to restore this sense of the primacy of altar and sacrifice. One of the means by which it sought to do so was through the revival of the altar covered by a ciborium. In many instances this still included the tabernacle being central upon the altar -- a sensible development (and compromise if you wish to call it that) that married the ancient Christian model with the counter-reformation. However, when versus populum came in vogue amongst progressive liturgists, this presented a problem. At cross purposes now was the counter-reformation's emphasis upon the Real Presence (in response to the Protestant Reformation and its own Eucharistic theories) and the progressive liturgist's archaeologistic tendency to give primacy to the most ancient liturgical models, in this instance the ancient basilica arrangement with its central sedilia and a freestanding altar beneath a ciborium. Let's be clear, these arrangements are both equally noble and Catholic arrangements, however the (unofficial) attempt to impose a basilica model on every parish church created immense difficulties and logistical problems. Gone was the excellent marriage between a counter-reformation piety and the ancient Christian basilica model -- all premised around the seeming "need" for versus populum (erroneously presumed to be the universal and ancient practice). Soon too even the ciborium -- one of the very best revivals of the Liturgical Movement -- itself would be dispensed with.

Caught up in the midst of all of this was the popular Catholic perception that it was all about the tabernacle, often displacing the central importance of altar and sacrifice. As was the case around teaching of the office of the papacy and infallibility, an easy but lazy form of teaching tended to result in popular oversimplifications -- for while altar, sacrifice and Real Presence are intimately connected and interdependent, this must be said clearly, the latter tended to displace the former unofficially speaking. The result was that the rich eschatological concept and practice of ad orientem became popularly reduced to Mass "facing the tabernacle" and other similar theological mistakes. We would also see situations arise where the ciborium no longer covered the altar but instead just the tabernacle. This was as much a result of the aforementioned tensions around versus populum as anything else -- and a way sometimes of preserving the ciborium while trying to fit in these other elements -- but aside from not really fitting to the historical purpose of the ciborium, it also had the regrettable side effect of further reinforcing these popular theological misconceptions.

It is within this context that, nearly a decade ago, I asked Matthew Alderman to write a piece on this very subject. I reprint it here today as I think it is as useful and important as ever, not only for a proper understanding of Catholic liturgical arrangement, but also for a proper understanding of Catholic liturgical theology.

* * *

"Eucharistic Reductionism" and Avoiding Past Mistakes

by Matthew J. Alderman

|

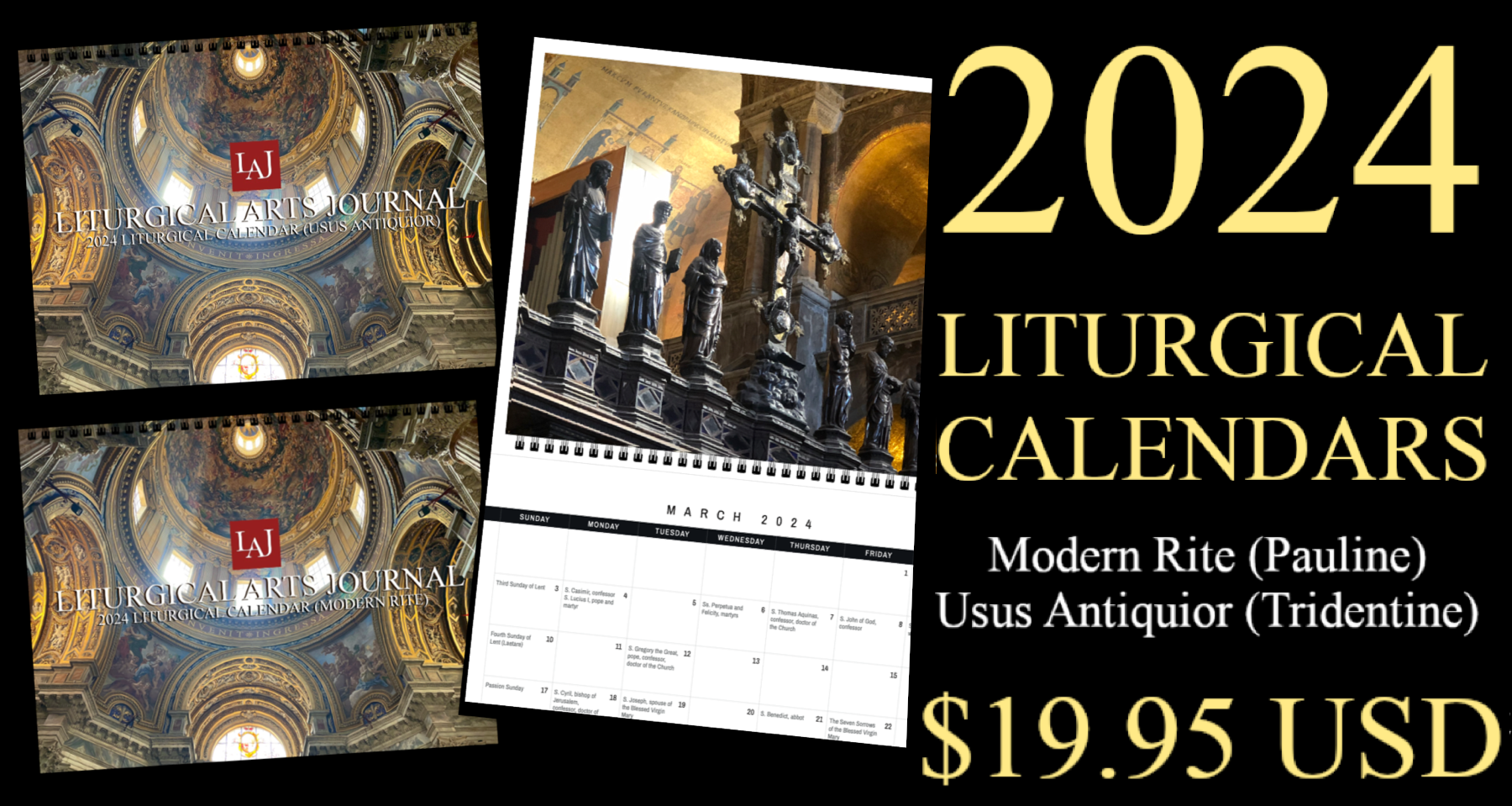

| Examples of well designed, oriented altars with (left) a dossal and tester and (right) a ciborium (sometimes incorrectly called a baldachin) |

The relationship between the tabernacle and the altar has, for the past two centuries, been one fraught with difficulties. The laity, particularly in America, frequently assume the elaborate wedding-cake altarpieces of the nineteenth century represent the fruits of some forgotten golden age; and indeed, they are not without their own charms, especially when compared with the Ikea modernism (and, unfortunately, occasionally Ikea classicism) that is the unique heritage of our own rather confused and cautious age. However, it is not without good reason that the rubricists of the Sacred Congregation of Rites and the enthusiasts of the twentieth-century Liturgical Movement, thought these highly interesting objects represented a sort of well-intentioned Eucharistic confusion. I do not say I agree with them per se, but read further.

At least one author has called the church of the nineteenth century a Eucharistic presence chamber, and not a true place of sacrifice--the reredos with its enormous and frequently unrubrical tabernacle overwhealming the little Great Aunt Esther's-style sideboard altar, an impression not improved on by overwhelming and badly-deployed flower displays. This can seem a rather peevish and petty response to the presence of God on earth, and perhaps such complaints sprang from the lips of oversensitive aesthetes and theological hair-splitters. Certainly we have gone to the opposite extreme since the Council, banishing the presence of God on earth to tiny broom-closet cenacles and reducing beautiful hand-carved retablos to liturgical backdrops, but at the same time, there is much to be said for such critiques. To simply reuse lightly-adapted nineteenth-century forms of liturgical planning is to solve a newish problem by returning to an older one and avoid the heart of the matter.

A number of old confusions have begun to re-surface, such as the claim that mass versus Deum is said thus so as to face the tabernacle. Mass is not an act of adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, but a propitiatory offering of It to the Father. (One is reminded of the strange habit of the Mariavite schismatics of requiring every mass to be coram Sanctissimo, which must have been very hard on the knees.) To claim otherwise reduces the unique beauty of Eucharistic adoration, Benediction, and our other acts of worship to Our Lord in the Host. There is room for both in our churches, but these theological distinctions are critical, lest the Trinitarian dimension of the Mass, and of Christ's role as mediator with the Father, be completely lost in the mind of the average Catholic. It is perfectly logical that we face the tabernacle during mass, of course, and it is the best solution to this complex liturgical issue, but historically it is not the sole or even principal reason for oriented worship.

Confusion over this complex relationship is particularly evident in instances where a new freestanding altar is retained, while the tabernacle is returned to its original location on the high altar, or even under a baldachin. This places the altar and tabernacle in competition, or perhaps even makes the tabernacle the central focus of the church to the exclusion of the altar. There is a reason, shortly before the Council, Pius XII thought it best that the tabernacle and altar ought not to be separated, precisely because it avoids this sort of quandary. I am by no means suggesting the tabernacle not be placed at the center and heart of our churches, but the altar must be placed there as well.

The later Liturgical Movement often urged the removal of the tabernacle to some other place in the church to restore the primitive purity of the altar, but by separating the two it seems to have merely confused people both about the role of the altar and the theology of the Real Presence. The wisdom of the rubricians is evident here: the altar is important liturgically; the tabernacle contains the most important Person on earth. Rather than seek to choose between the two, they simply brought them both together. Church restorations must weigh this relationship carefully, while remembering most parishes will still demand a freestanding altar with the tabernacle behind, rather than upon it, for pastoral reasons.

Some places will require a reredos behind a freestanding altar, which will be a natural place for the tabernacle. Some churches' sightlines absolutely demand it, and baldachins are comparatively more costly and can eat up valuable space in a small sanctuary. There is room for both ways in the Church. Indeed, I have designed one in the past (and seen it constructed) and I recently did some design work on another. There are ways to reproduce the old relationship in spirit, by creating a careful visual relationship between altar and reredos, ensuring the two work together rather than competing; some of this can be achieved by carefully watching the way space, and most importantly, floor levels, are defined within the chancel. The eye must also be drawn to the altar as well, and not simply up and over it. Careful use of color may also allow the freestanding altar to stand out against the reredos while retaining an integral relationship with it. A simple hanging tester over the altar may also be one possible solution, perhaps the best one; the reredos behind can serve as a sort of conduit between the two elements, altar and canopy. This may be the most ideal arrangement in many re-renovated churches, though where possible, the baldachin ought to be encouraged. In modernistic open-plan designs, it may give a sense of dynamism to low, centralized sanctuaries.

Clear mistakes, such as placing a tabernacle beneath a baldachin, and the altar some ways in front of it, rather lost and completely naked, should never be undertaken. I would much prefer a reredos as a tabernacle shrine with a freestanding altar than dump an altar in front of a gigantic baldachin covering only a tabernacle.

Attempts must be made, while allowing for the current liturgical climate, to bring the altar and tabernacle closer together spiritually, or even physically where possible, and find ways, through canopies and aedicules, to give appropriate honor to both. A nice balance of relative scales and placement--albeit one requiring some adaptation of its own--can be see in the image reproduced at the start of the article. (Of course, prudence should always be the first principle here: it is dangerous to mess with the Blessed Sacrament!)

As I said above, the wedding-cake catalog-bought reredos of most nineteenth-century churches has serious deficiencies from both a rubrical and theological perspective. First, most tabernacles of the period were not truly tabernacles, but sort of Eucharistic pigeonholes reminiscent of aumbries or sacrament-houses. Sometimes they may be the best choice for an interior, but a choice for them must be made knowing all the rubrical issues they bring up. There is a place for both of these in the tradition of the Church, and I don't object to their re-use, as they are often rather charming, but they do not represent the pure, rubrical, Roman tabernacle. This is a freestanding object capable of being placed on an altar or gradine shelf, usually cylindrical, and capable of being veiled on all sides. The tabernacle ought not to have a permanent Benediction throne on top of it (though a temporary one was deemed appropriate), nor be used as the base of a statue. A crucifix is best placed behind it, in line with the altarpiece's six candlesticks.

Such prescripts are no longer strictly-speaking required by law (in particular, the veil, which in some documents is considered optional though laudable; though there are some footnotes in the General Instruction that imply these practices have some degree of importance still) but nonetheless represent an important refinement of the tradition.

Reredoses, of the proper shape and emphasis, are an ornament to any church, especially smaller ones that cannot afford a ciborium. Simply pushing an altar up against a wall, adding a crucifix, tabernacle, candlesticks and a sufficiently nice dossal can change a whitewashed barn into God's temple on earth. But for the time being, the freestanding altar under the ciborium (or hanging tester), with the tabernacle somewhere behind, remains the best possible arrangement in parishes where both liturgy versus Deum and versus populum are likely to remain the norm, lest we compound new mistakes with older difficulties.